By: David Krubsack, PhD

“This is a football.” These are the legendary words from Vince Lombardi bringing the Green Bay Packers back to the basics and into a series of successful winning seasons. Similarly, documentation processes can become so complex that a simple understanding of what needs to be done can be lost. Bringing documentation back to its basic principles can help facilitate communication and efficiencies.

Documentation is necessary, not just because the FDA requires it for medical devices, but also because it just makes business sense. If you are successful building a prototype device, you will want to know how to build a second one. If there is a device problem you want to solve or an enhancement you want to make, you need to know where to start.

There can be confusion of how to document. This could be due to personnel coming from different backgrounds, all of which are legitimate documentation methodologies. There are different tools that can be used to assist in execution of the documentation. There could be a merger of companies with different documentation systems.

This confusion can create friction between departments. For example, the quality department may want to see certain documentation from the engineering department, yet while willing, engineering may receive conflicting direction on how to document. Or worse, following directions from personnel in quality may not be approved by all the signatories required to release the document.

Presented here is a technique that works well to resolve these kinds of confusion and conflict. It involves going back to the basics. My examples come from FDA regulations and medical device development, but the same basic principles can be applied in situations where there are documentation struggles.

We start with the FDA’s Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21 Part 820, and specifically Section 820.30f, Design History File (DHF). Consider this DHF to be a plant that is growing from the earth. Quoting the regulation, “The DHF shall contain or reference the records necessary to demonstrate…” All the references in the DHF are the roots underneath the plant, mostly invisible from the surface.

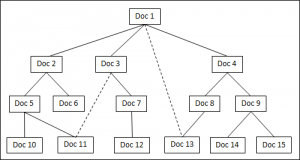

Using a root diagram (Figure 1), the DHF is the top block (Doc 1). Each block is a document. The rules of the game define lines coming out of the bottom of a block to be understood as “this document references another document”. Lines coming out of the top of a block are understood as “this document is referenced by another document”. No lines are allowed to come out of the sides of the blocks.

This may sound exceedingly simplistic and restrictive. However, if you are willing to agree to these rules for the duration of this article, I will do my best to explain how this can bring multiple departments together to solve documentation struggles in a dynamic and effective way.

It is possible that one document may be referenced by multiple documents in the root structure. In an attempt to keep complex cases simple, especially during dynamic live discussions on a marker board, every block should have only one solid line coming out of its top, and preferably connected to the longest string of referenced documents. For example, Doc 1 references Doc 4 which references Doc 8 which in turn references Doc 13. When it becomes more helpful than confusing, dotted lines can be added for additional references between documents. For example, Doc 1 directly references Doc 13. Whether there is a solid line, a dotted line, or no line in the diagram, the actual document will make any references it requires.

If the FDA appears on your doorstep asking for the DHF, what do you want this diagram to look like? This question should be asked as early as possible in the product development. The answer to this question will then help set the goals of the development.

It is often said, “If you didn’t document it, you didn’t do it.” Or to state it another way, it is done when it is documented. This simple concept equates tasks to documentation. Every task should end with a document. When the document is released, the task is done.

While it is very tempting to “run a quick test” in order to make a decision, the data upon which the decision is made will be lost if it is not documented. If any of you have spent time in remediation, you know these undocumented quick tests can add up to an exponential amount of work. So if a task does not ultimately end up in a document, the task has no value.

Now before you start listing non-documentation tasks that have value, please understand that often if task and document are not equated, it provides an excuse for not producing necessary documentation. Additionally, when it comes to review time, it becomes much easier to review your employees. You can pull up a list of documents that your team created, identifying both individual and team contributions. These efforts directly show relevance to the company objectives as they are referenced up to the DHF. Similarly, you can show your boss the objectives your team has accomplished.

Now that we have equated a task and a document, we can use these terms interchangeably. Just as electromagnetic radiation is both a wave and a particle, we can select the term most useful in context to clarify the discussion.

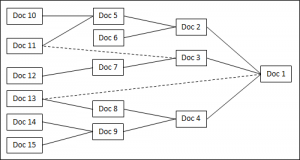

If we turn the root diagram of documents 90 degrees to the right, it becomes a PERT chart of tasks (Figure 2). In this case no lines are allowed to come out of the top or bottom of the blocks. Lines coming out of the right side of a block are to be understood as “this task must be completed before the task it is connected to”. Lines coming out of the left side of a block are understood as “this task can not be completed until the connected task is completed”.

We can assign people to the tasks, establish due dates, and identify dependencies. For those inclined to use Microsoft Project, there is a one-to-one correspondence. I would recommend adding one column to MS Project and label it “Document”. That way, it will clearly show what document is to be released signifying the completion of the listed task. MS Project can then create a PERT chart if so desired.

Using this technique, I have seen “tasks that must be done” wind up having no reference from the document structure and consequently being removed from the “task list”. Always good to not waste time doing things you don’t need to do. If the removed task is needed to complete a different part of the document structure, it can be linked there.

So what do we call this tool helping us visualize the DHF? Document structure? Root diagram? PERT chart? Task List? I like the term “Document Flow Diagram”. I mostly use the Document Flow Diagram in its vertical form (root structure) showing all the documentation containing the objective evidence in support of the DHF. Task assignments and due dates can be added to the vertical form just as if they would be added to the horizontal form and MS Project.

In my experience, the only time this technique has not worked is if people don’t want to play the game, or want to change the rules. Every time people are willing to play by the rules, it has always both unstuck the documentation struggles and clarified the direction of work.

This technique is not only effective, it can be dynamic and fun. It is visual, interactive, and gets everyone on the same page. It can be used independent of documentation systems or tools. As I touched on earlier, this method can be implemented using a marker board with relevant persons in the room. Once the rules of the game are understood and the basic documentation structure is outlined, I see people zeroing in on their scope of responsibility, naturally filling in details, assigning people and dates to the blocks, even in the vertical root diagram without having to redraw the diagram horizontally into a PERT chart. This makes the job of program management easier because a program manager can simply engage the participants with their scope of responsibility, either individually or in select groups depending on the issue under consideration. After the meeting, the program manager can enter the data from the resulting diagram into MS Project.

This can be used at multiple levels. Managers can use this technique to plan team objectives and execution. Once the individuals of the team understand the rules of the game, they can naturally use this technique amongst themselves to resolve detailed direction and milestones. Directors can identify and segment scope of responsibility for their managers by the higher level documentation that needs to be created. For VPs, much of these efforts can be delegated to the directors. However, it is important for VPs to support these efforts for directors and managers to be most effective in using the technique. VPs can use this technique amongst themselves to support the resolution of issues that require inter-departmental communication.

One such inter-departmental issue this technique can assist with is identifying and improving interrelated data and document control systems. Some quality systems allow for documentation to be captured in a written notebook. Some companies have a technical report documentation system outside of the quality system. Often there is an engineering release (Rev 1, for example) and a production release (Rev A). Volumes of electronic data are often maintained outside of the standard document control system. Enabling clinical data to be referenced is a must.

No matter how your formal documentation systems perform, they should allow a document to reference other documents. In one example I came across, the document control system allowed for reference to only documents in the document control system. It did not allow for references to controlled clinical data, clinical reports, published papers, or patents, all of which could be used in making a quality decision. As such, the relevant references needed to be buried within the document, not clearly presented in the “referenced documents” section. Your document control system should have a clear way to address this issue otherwise quality decisions will become untraceable.

Some of you may be saying: We are in early technology development and don’t need to document. We need to make sure the technology works first before investing all that time into a DHF structure because we are a start-up company with limited resources and funding. Once we are successful and sell the company, “they” will do all the documentation.

I agree, whether you are in a cash-strapped start-up or are in a large company managing cash flow, you need to be maneuverable and fast paced, able to innovate to stay ahead of the competition or simply to provide good product.

However, rather than a top down DHF discussion, think about the documentation you will need when you get to that point in your development and start documenting from the bottom up. Presuming your technology will be successful, you will eventually need to create a DHF so consider what supporting data and documentation you will need, and write those reports as you start your technology development. Then when the formal top-down DHF analysis takes place, you will be able to simply reference your early technology reports. Sure beats trying to recreate all your work during remediation.

If you want to sell the company, the purchasing company should be smart enough to know the cost of remediation and adjust the purchase price accordingly, presuming you have enough documentation to demonstrate to them that your technology works. If not, the purchasing company may choose to buy a similar technology where the documentation is sound.

It is often the case that if a structured discipline is not followed in the beginning, it costs more in the end. No matter how complex the problems get, keeping the basic rules simple helps focus efforts across departments at all levels. Staying disciplined to conform to these simple rules will help clarify direction and engage personnel.